I was thinking about Challenge vs Difficulty (particularly in cooperative board games) recently. At a glance, they sound like the same thing, but if you think about it, they're really not.

Definitions

I looked up "challenge," and the definition in this context is: "a difficult task, especially one that the person making the attempt finds more enjoyable because of that difficulty," while "difficult" is simply defined as "hard to do, requiring much effort." For the purposes of this post, I will sum those up as follows:

Difficulty in a game is the extent you're unlikely to succeed.

Challenge in a game is the extent to which overcoming the difficulty is fun or rewarding.

I've found that these terms come up a lot in the context of cooperative games, where the players need some sort of AI or algorithm to play against rather than the cunning and guile of a human opponent. A good cooperative game is challenging, it sets a task for the players, and they have fun trying to overcome obstacles to accomplish that task. One of the nice things about these games is that an optimal set of plays is not clear, and the whole point is to make that optimal set of plays, or close enough, that you achieve the goal of the game in the time allotted.

However, some cooperative games aren't challenging so much as just difficult. In those games, the chances of losing even with an optimal set of plays is too high, so it doesn't feel as fun or rewarding when you win.

The Components of Difficulty

There are 2 major things that can make a game more difficult - they both reduce your likelihood of winning: Increased depth, and decreased fairness, where depth is the amount of good play required to win, and fairness is the degree to which that good play determines the outcome.

- In a fair game, the outcome is less often dominated by factors outside your control. If you play well, you'll win more often.

- In an unfair game, too often the outcome is outside the player's control. There's a significant chance you'll lose even if you were to play optimally

- A deep game has a high skill ceiling. You have to build up to the point where you can hope to play near-optimally

- A shallow game has a low skill ceiling. You can be confident your play is near-optimal without too much time, effort, or study

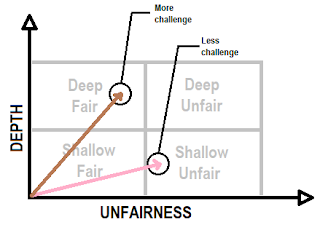

In order to examine this more closely, I thought I'd make a graph of Depth to Fairness. Plotting a game on that graph could allow us to visually see some of these relationships and make sense of them:

WAIT! Why am I using UNfairness on the bottom axis instead of Fairness? Difficulty comes from both depth and unfairness. A deeper game is more difficult to win because it requires better play. A more unfair game is difficult to win because despite good play, you might lose due to chance. So both of those things can increase difficulty. I use Unfairness for the axis so that moving away from the origin in either direction makes the game harder.

Now we can locate games on the graph, draw a vector to them from the origin, and the length of that vector relates to how hard the game is to win:

Magnitude = Difficulty

"Challenge," then, is how fun or rewarding it is to overcome that difficulty. In this graph, the slope of that vector (rise over run: depth over unfairness) relates to the amount of challenge the game has to offer. The deeper the game, or the fairer the game, the more rewarding it is to overcome its difficulty, and therefore the more or better challenge it presents.

Practical Application

Let me lay some ground rules on what this graph applies to, how it can be helpful, and what it's limitations are.

For one thing, you'll notice that there are no numerical values on these axes. I am not sure how these aspects could possibly be measured! Also, those gray, labeled boxes are completely arbitrary, and can be deleted or redrawn wherever you'd like, so a single data point on this graph is meaningless. This graph only allows us to make relative comparisons between multiple games. As soon as you get 2 data points, you can begin to compare them and see, in a qualitative sense, which is more Fair, which has more Depth, which is more Difficult, and which is more Challenging.

This information might work best for 1-player games, solo modes, and co-operative games, when the "opponent" has a consistent skill level. It does not make as much sense for a multiplayer game, where the difficulty depends on your opponent's skill level as well - although you might be able to gain insight into questions like "how hard/challenging is it to play various different games vs Steve?" If the opposition is fixed as that particular opponent for each game, then I think the model will still allow comparisons, which could be fun to do amongst a group of friends who play vs each other a lot.

Similarly, I think this could be used to compare factions or characters in an asymmetric game - not in general, but if you look at various factions/characters vs a particular faction/character, then you might be able to glean some useful balance (or strategic) information about matchups.

Something I think might be a stumbling block in reading this graph is that we're not talking about the outcome of a particular match here. We're talking about the difficulty of the game in general -- overall win rates, not whether you win or lose this instance, or this play of the game.

A Worked Example

Pandemic is a popular cooperative game for 2-4 players, and you can adjust the difficulty from "easy" to "expert" by using 4-6 Epidemic cards in the deck. The game is obviously harder with more Epidemic cards, but I've also observed that the game gets harder the more players you have due to logistical concerns. Let's take a look at some of the configurations you can play Pandemic in, and plot them on this Difficulty chart:

The way I drew that I'm saying that 2p-expert and 4p-easy are approximately the same difficulty, but in 4p it's more rewarding to overcome that difficulty

Good Difficulty vs Bad Difficulty

We have learned that Difficulty comprises two aspects: Depth and Unfairness. One of those increases Challenge, and the other does not, but both increase difficulty. I don't think I'm out on a limb saying difficulty that increases challenge is "Good Difficulty," and difficulty that does not increase challenge is "Bad Difficulty."

There do exist cooperative games where added difficulty does not seem to increase the challenge. I remember when Ghost Stories came out, it was the talk of BGG.con that year, and all the buzz was that the game was really difficult. After finally playing Ghost Stories I remember thinking "I'm not sure a higher chance you can't win is the kind of 'difficult' you want in a game." Of course, that hasn't stopped the game from being incredibly popular over the years!

I've recently gotten to try

The Princess Bride Adventure Storybook Game, and it strikes me as a game with a low skill ceiling. It's fairly easy to figure out what to do, and you can go through the motions to do it, and then you see if you were able to finish in time. You can reach the point where you can achieve optimal or close-to-optimal play with some confidence, but even with optimal play, often whether you win or lose a chapter seems to come down to chance. In this game's defense, I've only played it with 2 players, and it's possible that, like Pandemic, the game is more challenging (or at least harder) with more players.

To be fair, that's always the case with cooperative games -- given optimal play, there's still a chance you'll lose the game. Most (all?) cooperative games have that dynamic, lest they become "solved," and that's probably a good thing. But perhaps each game has an Unfairness threshold, a percentage chance that you lose anyway, even with optimal play, that is acceptable. Under that threshold, the game could be considered "Fair" (or fair enough). Above that threshold, the game could be labeled "Unfair." In a good cooperative game, the amount of Unfairness would be closer to that threshold, whereas in a bad game, the Unfairness might be much higher than the threshold. Unfortunately, I don't have a good feeling for where that threshold should be, and it is almost certainly different from game to game.

Conclusion

The best case scenario in my mind is a deep/fair game, where winning correlates to amount of good play, and the chance you lose even with good play is within acceptable limits. This offers more challenge, and it's therefore more rewarding and more fun to overcome the difficulty. A bad game in my mind is one that is shallow and unfair, where winning does not take much good play, but does require a lot of luck.

I'll try to keep this difference between "challenge" and "difficulty," and this Depth-to-Fairness ratio in mind when designing, especially when working on a cooperative game. For example, if I ever finish up Alter Ego, maybe I'll apply these lessons to ensure that to the extent the game is difficult, it provides "good difficulty," not "bad difficulty." It's important for games to be challenging, not just difficult!

Post Script on Effort

Another thing that could be considered is when a game requires more effort: doing lots of simple math, moving pieces around, grinding actions, that sort of thing. Busywork. Since these things don't require any particular skill (except maybe stamina to endure them), I'm not sure they make a game harder to win, they just make it more annoying to play. They could be said to reduce the Challenge, because they make it less fun and rewarding to overcome the difficulty of the game, but they do not themselves contribute to the difficulty. Therefore I don't think we need to consider Effort in this model.